Unaccompanied Baggage Inspection application has a positive impact on On-Time-Performance by reducing delays, costs and emissions

As air travel starts to regain momentum, operators will once again face the challenge of minimising the time delays and costs associated with unaccompanied baggage. Based on pre-pandemic air traffic volumes, it has been estimated that globally this issue costs airlines 732,564 minutes (or 509 days) and $62 million dollars per year*.

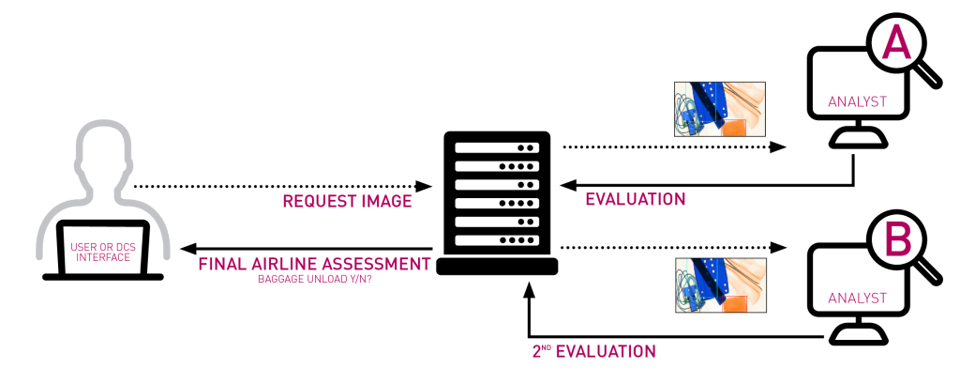

Since the 1980s, the baggage reconciliation rules have demanded the removal of any unaccompanied bags from the aircraft before take-off. With the introduction of EDS screening technology, the regulations have been amended to allow the baggage to remain on board if the original security screening images are reviewed and cleared by one or two operators.

“We were keen to make the recheck process more efficient and had recently seen the Smiths Detection Unaccompanied Baggage Inspection (UBI) software in action at another major European airport ,” commented Thomas van de Plassche, Security Process Developer, Royal Schiphol Group. “So we decided to run trials at Schiphol Airport to investigate if UBI could have a positive impact on our operations.”

Having identified an unaccompanied bag by its IATA code, UBI software sends the relevant, original screening image to a qualified security operator. Results are automatically routed back and if clear, the plane can take-off.

“Our primary goal was to increase airline OTP (on time performance). Removing hold baggage causes delays – the cost in fuel alone is significant; additional emissions have a negative environmental impact; and the passenger experience also suffers,” added van de Plassche.

Fast and effective

The Schiphol trials started with a one month ‘non-live’ shadow period using dummy bags to demonstrate to the airport and the regulators that the UBI application was compliant and would fit easily into existing operational models. It then went live for three months at the end of 2020.

“Due to the pandemic, there were a limited number of flights available for the trials. From our sample, around 20% had unaccompanied baggage,” explained van de Plassche. “We focused on improving the process when incidents are passenger driven (e.g. late to the boarding gate) rather than those outside of the passengers’ control (when there is a clear operational explanation why the baggage is unaccompanied and it does not have to be removed from the aircraft). Making this distinction alone had a very positive impact on the efficiency of the overall procedure.”

“We started by preselecting those influenced by passengers as these would qualify for re-checks using the UBI module. Over half fell into this category and would typically have to be offloaded – but not so with UBI which becomes a key step in the overall airport security process, speeding up the secondary inspections and ensuring it complies with local security regulations.”

In the trial, 52% of the luggage sent for a recheck was cleared using the UBI system and could remain on board, enabling the flights to meet their OTP. Inspections of the remaining 48% proved suspicious or inconclusive and therefore had to be removed from the aircraft.

Key findings

“We found that the UBI application does what it promises in streamlining the image re-evaluation and therefore improves process efficiency. Clearing 52% of passenger driven incidents without causing delays significantly reduces costs, increases OTP, improves the passenger experience and avoids additional emissions. To achieve optimum results, it is important for each airport to establish its own appropriate operational model,” concluded van de Plassche.

Network integration was very simple as Schiphol is already equipped with the Smiths Detection server and only required activation of the UBI software. Deployment is generally straightforward for any airport with networking capabilities.

*Figures compiled by Westland Advisory by assessing data from governments, NGO, professional services organisations and academic studies.